Table of Contents

How Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan's anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Süss (1940) shaped a nation's hatred and left his family grappling with guilt across generations.

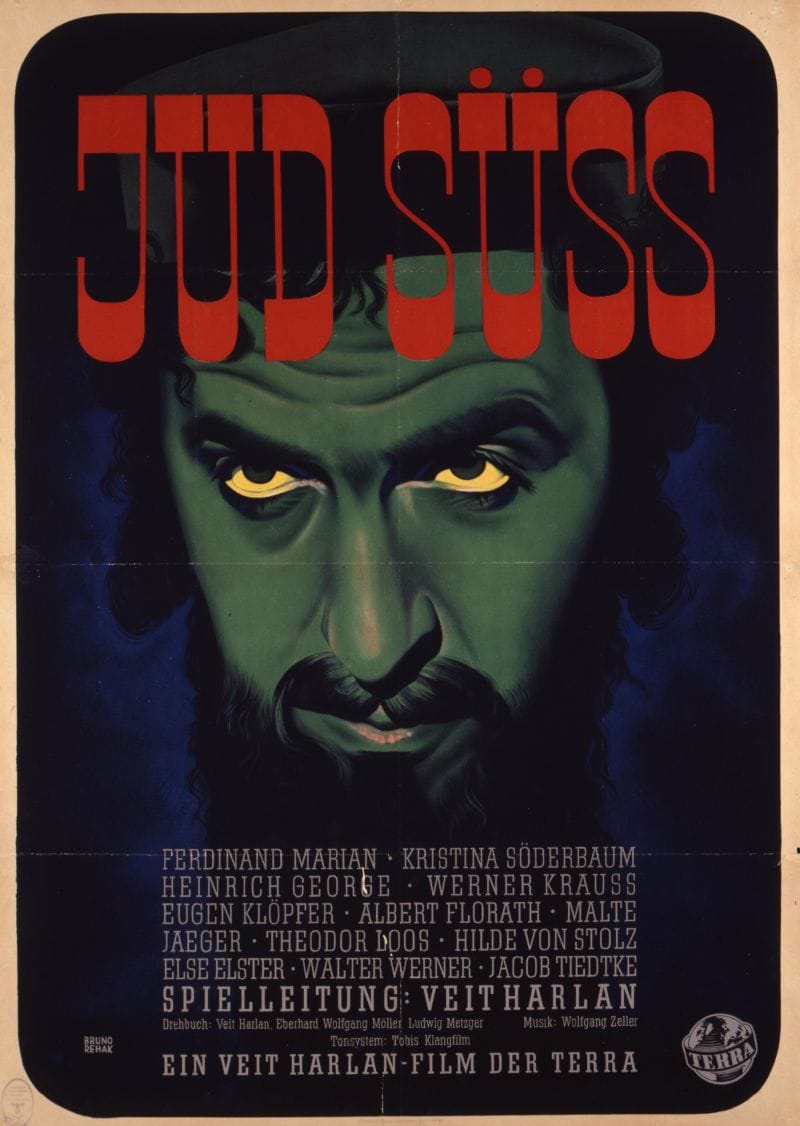

Several years ago at our weekly village film screening, we watched the documentary Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss (2008) about Third Reich propaganda filmmaker Veit Harlan, whose controversial film helped inspire a nation to persecute and murder Jewish people. I had not heard of Veit Harlan before viewing this documentary, but it immediately became clear that his work, particularly Jud Süss (1940), was infamous throughout Europe.

Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss (2008) documentary trailer

Harlan and his actress wife Kristina Söderbaum enjoyed status in Third Reich Germany similar to that of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks in Hollywood. His films were screened in cinemas across Germany and Europe, whilst Söderbaum, a beautiful Aryan blonde, became famous for her woman-child characters and tragic screen deaths. They and their children lived a life in Germany of privilege before, during, and after the war, while many other German filmmakers chose to leave Europe when the Nazis rose to power.

Harlan's collaboration with the Nazi regime

Harlan became closely affiliated with the Nazi Party, working directly with Joseph Goebbels to produce anti-Semitic propaganda films. Harlan proved an ideal collaborator for Goebbels’ vision, possessing both the technical skill to create compelling narratives and the willingness to embed them with Nazi ideology.

Harlan had already established himself as a successful theatre director and actor by the time he was approached to collaborate with the Nazi Party. His transition to film direction in the 1930s coincided with the Party's increasing control over German cultural production. Rather than resisting or emigrating like many of his contemporaries, Harlan embraced opportunities within the new regime, eventually becoming one of the Third Reich's most trusted filmmakers.

The propaganda machinery of Nazi cinema

The Nazi film industry operated as a sophisticated propaganda apparatus. Goebbels understood that heavy-handed political messaging could alienate audiences, so the regime preferred films that appeared to be conventional entertainment whilst promoting Nazi racial ideology.

Examining Jud Süss as anti-Semitic propaganda

After viewing the documentary, I managed to get my hands on a copy of Harlan’s Jud Süss and watched it (not to be confused with the more sympathetic 1934 British version starring Conrad Veit). The film presents itself as a period drama set in 1770s Stuttgart. A new duke assumes leadership and takes a solemn oath to protect his people, earning celebration and respect from his countrymen. When the duke faces financial constraints that prevent him from funding such extravagances as an opera, ballet, and personal guard, he turns to a wealthy Jewish man named Joseph Süss Oppenheimer from outside Stuttgart for financial assistance.

The narrative structure deliberately establishes the duke as virtuous and his subjects as innocent before introducing Süss as a corrupting force. Misguided by greed, the duke allows Süss to gradually assume control of various political matters, including road taxation. The film portrays Süss using this power to abuse Stuttgart's citizens and open the city gates to other Jewish residents, historically denied entrance to the city. According to the Nazi propaganda narrative, these newcomers bring crime, licentiousness, corruption, and moral decay.

The climax occurs when Süss assaults the chairman's daughter, causing her death. The citizens, led by the duke's dissolved council, rise in rebellion. Süss receives a brief trial in which he lies and denies all guilt, then faces execution by hanging.

Dehumanisation through visual and narrative stereotypes

The film presents Jewish characters through grotesque caricatures designed to inspire revulsion and fear: they appear with exaggerated hooked noses, small glittering spectacles, and greasy appearances. They are depicted wringing their hands and hunching forward whilst walking, reinforcing medieval anti-Semitic tropes about Jewish people's supposed physical abnormalities.

The film not only attacks what the racist Third Reich was as cultural differences; it goes after the core of Jewish religious practises, portraying filthy, packed synagogues where worshippers writhe and wail in chaotic and heathenish anguish. All Jewish people in the film are shown as inherently evil and corrupted, requiring first prevention from entering the country, then expulsion once they are in by hunting down and killing "like rats."

This progression mirrors the actual escalation of Nazi policies from exclusion to deportation to extermination. Contemporary evidence suggests the film succeeded in its propaganda aims. Jud Süss was screened to SS units before they participated in mass killings, and audience reactions documented at the time reveal how effectively the film generated hatred.

Post-war accountability and the problem of artistic complicity

After the war, Harlan was among the few filmmakers brought to trial for his participation in Nazi propaganda efforts. He faced two counts of crimes against humanity but was acquitted, though many questioned whether justice was served given the broader context of post-war denazification proceedings. The judges themselves were often compromised figures, and the legal system struggled with questions about artistic responsibility for political outcomes. Harlan's case became a precedent for debates about whether filmmakers could be held legally accountable for their works' ideological effects.

Harlan continued making films after his acquittal, albeit without the financial support and official backing he had enjoyed through Goebbels. His post-war work largely avoided political themes, focusing instead on melodramas and literary adaptations. However, his reputation remained permanently tainted, and many in the film industry refused to work with him.

He persistently denied guilt throughout his life, claiming Goebbels forced him to make such films and that he had no choice but to comply with the more powerful Party apparatus. This defence became common among Nazi collaborators, but evidence suggests Harlan's collaboration was willing and enthusiastic. His technical mastery and narrative sophistication in Jud Süss indicate someone fully committed to the project's ideological goals rather than a reluctant participant.

Family guilt and generational trauma

The documentary Harlan: In the shadow of “Jud Süss” reveals how Harlan's children and grandchildren continue confronting guilt left in Jud Süss's wake. They grapple with fundamental questions about their patriarch's moral responsibility:

If he was compelled to make it, why did he craft it so effectively and convincingly?

Why did he cast his wife in a film with such explosive themes unless he felt unthreatened by opposition to its message?

Why did he not acknowledge that he made these films merely to survive under the Third Reich?

The family's reckoning becomes more complex when considering that Harlan's own first wife and her family perished at Auschwitz. This personal connection to Nazi genocide raises additional questions about his awareness of the regime's crimes and his willingness to participate despite understanding the consequences. His collaboration with those orchestrating mass murder seems certain, particularly given his direct relationship with Goebbels and other high-ranking officials.

The most troubling question remains:

How aware was he of the concentration camps and extermination programme?

Given his position within the Nazi cultural apparatus and his personal losses, ignorance seems implausible.

Different responses to inherited guilt

Harlan’s family members appear to be processing their inherited guilt through various strategies. Some, like filmmaker son Thomas, have moved completely in the opposite direction, becoming liberal advocates and contributing to efforts tracking other Nazi war criminals. Their political activism represents an attempt to atone for their father's crimes through opposing contemporary fascism and racism.

Others, including his actress daughters, were compelled by their agents to change their surname because no one associated with the Harlan name could secure work in the post-war film industry. This practical response acknowledges the lasting damage to their family reputation whilst attempting to separate individual identity from collective guilt.

Broader implications for understanding propaganda and complicity

Veit Harlan's family story represents the tensions that continue to affect German society after the war. The pursuit of justice for an entire people who either subscribed to Nazi propaganda's messaging or fell victim to it continues today. Understanding Harlan's case illuminates how ordinary people become complicit in genocide through cultural production and consumption.

The case of Jud Süss presents particular challenges when examining an artist who encouraged destruction. The work appears clearly deliberate, created by someone who understood both filmmaking techniques and their potential psychological effects. Questions about retrospective interpretation cannot diminish the documented evidence of the film's role in preparing its audiences for genocide.

Whilst many Hollywood war films may appear problematically jingoistic when viewed with a critical eye, drawing equivalencies between general propaganda and genocidal messaging risks diminishing the specific harm caused by Nazi cinema. Jud Süss was explicitly designed to facilitate mass murder, making it qualitatively different from films that merely promote nationalism or patriotic values.

Only through continued education, honest confrontation with uncomfortable truths, and a strong commitment to humanity's capacity for moral growth can the scars left by the social injustice and horrors of the Holocaust find healing. Understanding how propaganda works—and how artists can become complicit in atrocities—remains essential for preventing genocide in the future and protecting vulnerable communities from dehumanising cultural messages.